Looking Back – The Inagua National Park: A Conservation Success Story

Inagua National Park, on the island of Inagua, covers 287 square miles ( almost half of the island ) of Great Inagua. Bird life dominates the park, and the flamingos, the national bird of The Bahamas, is the star of the show. The park is home to over 50,000 West Indian Flamingos, one of the largest breeding colonies in this hemisphere. After 60 years the birds are back from the edge of extinction.

Inagua Flamingos – mass feeding

In 1905, at the first annual meeting of the National Audubon Society, a plea was made to The Bahamas government for the establishment of legal protection for the flamingo. Almost immediately the Wild Birds Protection Act was passed. In 1922, The Bahamas set aside a flamingo reserve on Andros Island and Audubon sent a patrol boat to help the wardens patrol the reserve. Flamingos continued to nest in Andros until World War II when Royal Air Force pilots buzzed the bird colonies for fun.

Flamingos were not only hunted for food, but also for their exquisite plumage. Indiscriminate hunting led to the disappearance of the flamingo in Florida Bay- last seen there in 1903.

Robert Porter Allen

By the 1950s, a close working relationship had been established between the National Audubon Society and The Bahamas. Concerned with the sudden decline of the flamingo population during the early years of that decade. Audubon sent Robert Porter Allen, its Research Director, to investigate the situation. All of the places where flamingos were rumored to nest in the Caribbean – Cuba, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic- were searched. Owing to pressure from an expanding human population, fifteen colonies had been abandoned in the Caribbean over a period of 35 years. However, stories persisted about a great colony in the inhospitable wilds of Great Inagua.

Together, Bob Allen and Sam Nixon, a local hunter, found more than a thousand flamingos “commulating”. The birds massed in a riotous courtship ritual of head turning, wing flicking and exaggerated strutting- “the Flamingo Quadrille”. Bob Allen had found the population that might one day replenish the long-abandoned colonies elsewhere in the Caribbean. The Society for the Protection of the Flamingo in The Bahamas was formed by American and Bahamian Conservationists. Sam Nixon became the first flamingo warden on Great Inagua, with the National Audubon Society providing funding for his salary and equipment. On a subsequent trip in 1956, Bob Allen wrote a monograph that is the basis of much of our knowledge of the “Caribbean” flamingo’s natural history. By an odd twist of fate, it is not direct human persecution that is the major threat to Great Inagua’s flamingos but the marauding wild pigs that were introduced by early settlers. These “wild hogs” feed on the birds eggs and young. Constant vigilance and regular monitoring by the wardens have done much to neutralize the threat.

Samuel Nixon, Alexander Sprunt IV and Jimmy Nixon on the camp at Jackass Cay.

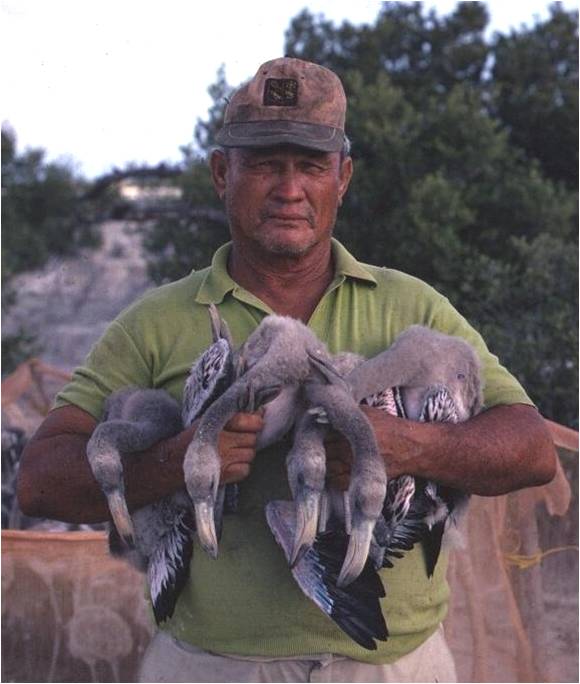

Jimmy Nixon, warden of the Inagua National Park. An accomplished hog hunter.

Another positive step was the creation of the Bahamas National Trust(BNT) by an Act of Parliament in 1959. As the official organization responsible for national park management providing support for wildlife management, the Trust took over the work of the old Society of the Protection of the Flamingo. By working closely with Morton Salt ( business enterprise engaged in solar salt manufacturing), various government agencies and the National Audubon Society in a mutual aid partnership, the BNT has helped the resident flamingo population grow from several thousand birds in 1952 to over 50,000 birds today.

Samuel Nixon, first warden of the Inagua National Park

Sam Nixon with young flamingos.

Morton Salt produces salt by solar evaporation in the vast flat saltpans that traverse the Inagua landscape. The process takes two years for seawater to be circulated from pan to pan. In time, algae, fertilized by the flamingo droppings grows in the water and darkens it.

This hastens evaporation by absorbing more sunlight. Then the tiny brine shrimp begin feeding on the algae cleaning the water. And the flamingos feed on the shrimp until the salt is ready for harvesting leaving both the flamingos and people tickled pink! – A wonderful example of how private enterprise and Mother Nature can join forces. Furthermore, Morton assists the BNT by providing an office, keeping the dike roads passable and other infrastructure in good condition. Having learned a lesson from the disappearance of the flamingos on Andros, the Bahamas Government has made the air space of above the Inagua National Park, a restricted area, banning flights below 2,000 feet.

Counting Nest Mounds

Salt mountain Inagua

The success of the Inagua National Park is evident in the restocking of other Caribbean islands by the Inagua flamingo population. Scientists are aware of the link between healthy flamingo populations in Inagua and Cuba, as well as between Inagua and the Turks and Caicos Islands, Grand Cayman, the Yucatan in Mexico, Crooked Island and Acklins.

Flamingo and just hatched baby flamingo.